U.K. researchers have reportedly demonstrated the safety and efficacy of the artificial pancreas in Type II diabetes patients in a general hospital ward. The team’s work was published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

U.K. researchers have reportedly demonstrated the safety and efficacy of the artificial pancreas in Type II diabetes patients in a general hospital ward. The team’s work was published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

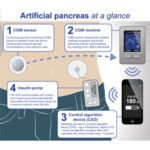

The closed-loop insulin delivery system can monitor blood sugar levels and change the insulin delivery rate accordingly, without the need for skin-pricks and manual insulin injections.

The artificial pancreas “allows more responsive insulin delivery and the expectation, so far supported by clinical studies, is that health outcomes can be improved,” senior author Dr. Roman Hovorka, of the University of Cambridge Metabolic Research Laboratories, told Reuters. Hovorka pointed out, however, that it costs more than injections and requires patients to constantly wear the device.

The U.K. researchers enrolled 40 adults with Type II diabetes who were receiving insulin therapy. Half of the group received their usual insulin injections for 3 days, while the other half received closed-loop insulin delivery using the artificial pancreas.

The artificial pancreas used a glucose sensor, which was inserted beneath the skin, to measure blood glucose levels every 1-10 minutes and used that data to determine how much insulin to deliver.

Patients with the closed-loop delivery system spent 60% of the 3-day period in their target blood sugar range, as opposed to the average 38% for the time in the control arm. There were no incidents of severe high or low blood sugar in either arm and no other adverse events were reported, although the study was considerably small.

“We presently use the closed loop system in people with type 2 diabetes staying in hospital,” Hovorka said. “Glucose control in hospital is often suboptimal and our aim is to improve it while people with type 2 diabetes are staying in hospital for various reasons such as treating diabetes complications.”

Before all Type II diabetes patients can have an artificial pancreas, “the major issue will be demonstrating cost effectiveness, through larger clinical trials, given the continual push on health care expenditure,” he told the news outlet. “Development of commercial systems specifically for type 2 diabetes is also a necessity.”

Gerry Rayman, of Ipswitch Hospital NHS Trust in Suffolk, U.K., wrote in a commentary accompanying the study questioning if the results would play out the same way under real-world conditions. Very often, he wrote, hospital admission of diabetics are emergencies unrelated to diabetes and patients are cared for by people other than diabetes specialists. Even diabetes specialists can have a hard time learning to insert and calibrate the glucose sensors, Rayman wrote.

But despite the challenges, Rayman wrote that controlling diabetes in the hospital setting is an important problem to solve.