Researchers say the animals’ immune systems accepted the donated cells prior to transplantation. This occurs through a three-pronged process they say they could easily replicate in humans. The mice did not need immune-suppressing treatments after the transplant to prevent the rejection of foreign islet cells.

“Clinically, the implications are very promising,” said professor of developmental biology Dr. Seung Kim. “There are many people with diabetes in the world who would benefit from receiving islet cells.”

According to Stanford, islet transplantation requires chronic immune suppression, most commonly with drugs. Methods for preparing immune systems for transplantation exist, but typically involve high-dose radiation and chemotherapy. These methods can be too toxic for most people with diabetes. Kim said the research allows for the use of an unrelated donor to avoid the toxic methods.

Kim directs the Stanford Diabetes Research Center and the JDRF Center of Excellence. He served as senior author for the study, published Nov. 8 in Cell Reports. Former postdoctoral scholar Charles Chang and graduate student Preksha Bhagchandani served as lead authors. They believe the findings could reach beyond diabetes. The technique could offer a new avenue in organ transplantation that doesn’t require an immunologically matched donor or years of immune-suppressing medication.

The two-transplant method for “curing” diabetes and beyond

Stanford developed a method to perform two transplants instead of one. This features the replacement of the recipient’s immune system with that of the organ donor. This occurs through the process of a blood stem cell transplant. Prior to organ transplant, this ensures the organ will be viewed as “self” and the body won’t reject it.

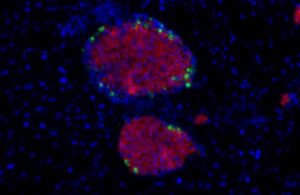

The researchers developed a “hybrid immune system.” It features both donor and recipient stem cells, plus a reduced likelihood of graft-versus-host disease.

They say hybrid immune system is less likely to reject the transplanted organ, especially if immunologically well-matched. Until now, the conditioning regimen to accomplish this appeared too harsh for use in non-life-threatening situations. In these cases, organs had to be at least partially immunologically matched to avoid the drugs.

The steps

Kim and the team developed a “three-pronged” approach for diabetic transplant recipients. It features low-dose radiation with one dose of the c-Kit antibody and another antibody targeting mature immune cells. This allowed donor cells to establish themselves in animal bone marrow and create a fully functioning chimeric immune system without severe side effects.

The animals with diabetes accepted a transplant of islet cells from the donor, even if they didn’t have an immunological match.

“We had a notion that we could get the bone marrow ready to accept the donor stem cells with less toxic, alternative approaches,” Kim said. “We found we could reduce the radiation dose by 80% and replace broad-acting chemotherapy drugs with targeted antibodies. The animals rapidly gained back the weight they had lost due to the disease and were able to maintain normal blood glucose levels until the study ended after more than 100 days.”

Success in this method could offer diabetes treatment at an early age. It may prevent or mitigate a lifetime of health problems, the researchers say.

Mice demonstrated no higher susceptibility to infection than control mice. This showed normal function in their immune systems, plus the ability to breed and birth healthy pups.

The researchers cited a caveat that the donor stem cells and islet cells must come from the same animal. This represents a difficulty as human islet cells are difficult to procure. Kim and colleagues seek to investigate whether functional islet cells could be created in the laboratory from pluripotent stem cells. Additionally, they aim to see if human islet cells can be grown and expanded in the laboratory to make more transplantable islet cells.

“This is exciting for many reasons,” Kim said. “This approach could be applied to autoimmune diabetes, including type 1 diabetes, and suggests that completely mismatched islet cells could be used for transplant. Beyond diabetes, it has important implications for solid organ transplants.”