Major players in the medical device realm are in a heated race to develop the first artificial pancreas to help patients with diabetes manage the chronic condition. Just last year, Medtronic (NYSE:MDT) won FDA approval for its MiniMed 670G hybrid-closed loop system.

Major players in the medical device realm are in a heated race to develop the first artificial pancreas to help patients with diabetes manage the chronic condition. Just last year, Medtronic (NYSE:MDT) won FDA approval for its MiniMed 670G hybrid-closed loop system.

But while companies compete for the top spot in developing what could be a fundamental change to diabetes management, Paul Strasma and Dr. Jeffrey Joseph of Capillary Biomedical are focused on optimizing one particularly important part of the system – insulin infusion.

Insulin pumps have been around for decades. But when Strasma and Joseph went to the JDRF in 2014 in search of support for their newly-formed company, the diabetes fund told them they were finding an array of issues with insulin delivery in artificial pancreas systems.

Patients were being asked to replace their steel catheters every 2 days or their Teflon catheter every 3 days. Even then, companies were reporting variability from dose to dose. And that’s particularly bad when it comes to a dose of insulin, which needs to be highly optimized for people with diabetes.

Strasma and Joseph were no strangers to diabetes – they previously worked together on blood glucose sensor technology. When they heard that insulin delivery was a problem, they recalled that wound response turned out to be important with glucose sensors. On a hunch, they decided to investigate if inflammation mattered in insulin infusion.

Fast forward to this year’s annual meeting of the American Diabetes Assn. and the team at Capillary Biomedical have early clues that inflammation plays a critical role in influencing insulin delivery.

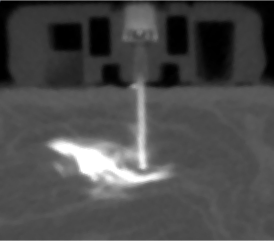

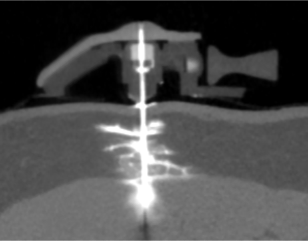

Using micro-CT imaging and continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion catheters in a swine model, researchers were able to assess the distribution patterns of insulin delivery over the course of 7 days.

The company found that inflamed tissue around the entry-point of the catheter is an obstacle to delivery, but that’s hard to avoid. Every time a device needs to get through a patient’s skin, there will be inflammation.

The more surprising finding, Strasma told Drug Delivery Business News, was that when the catheter kinks and creates sharp edges, the body reacts harshly even to soft materials like Teflon.

“We were stunned at the amount of inflammation at the point of the kink,” Strasma said.

The team observed that inflammatory tissue forms a dense layer that creates pressure and prevents the insulin from getting to healthy vascular tissue near the site of injection.

To solve this problem, Capillary is developing a catheter that is wire-reinforced to prevent kinking and made from a soft, flexible material that Strasma and Joseph described as “limp spaghetti.” The company is still in preclinical studies and is racing to get their drug delivery system into the clinic by the end of the year.

Joseph pointed out that this problem with insulin infusion can likely be traced back to the very first insulin pumps, but nothing substantial was ever done about it.

“No one’s made an effort to put science behind it, despite it being a real clinical issue,” he said.

“There was a period of refinements in the ’80s where they went from steel needles to Teflon cannulae, but it very quickly got to the point of ‘good enough’ and ‘don’t go looking for problems,'” Strasma added.

Moving forward, the team at Capillary plans to seek out strategic partners as they consider the potential regulatory and commercial pathways for their device.

“We know that to go through the regulatory process and get this to commercial use, we need to be very close with the insulin pump manufacturers and the insulin drug manufacturers as well,” Strasma said.

He pointed out that the industry has largely left the issue of insulin delivery behind, moving on to develop smarter pumps and insulin products that absorb better.

“We’re the company that said, ‘wait a minute, what about the plumbing?’ Because if the drain is clogged, your better insulin doesn’t get absorbed and your algorithm doesn’t work because the insulin didn’t even go in,” Strasma said. “We like to think of ourselves as plumbers fixing the drain.”