Scientists at Washington University (St. Louis) and Cornell University (Ithaca, N.Y.) successfully implanted insulin-secreting cells in mice with type 1 diabetes. The cells proved capable of reversing chemically-induced diabetes for up to 200 days after implantation, according to a recent article in Science Translational Medicine.

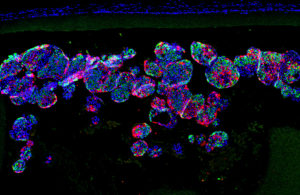

To do so, they used a nanofiber-integrated cell encapsulation (NICE) device containing insulin-secreting β cells. Researchers can produce such cells by modifying stem cells from skin or fat tissue.

One of the traditional challenges of using such an approach is that the immune system tends to destroy externally introduced insulin-secreting cells.

To protect them, the researchers decided to use the micro-porous NICE device, whose pores are sufficiently small to prevent immune cells from entering yet large enough to allow nutrients and oxygen to enter while preventing cellular overgrowth. The researchers “tuned” the nanofibers to approximately 500 nanometers.

Made of thermoplastic silicone-polycarbonate-urethane, the experimental device features a nanofibrous skin with a hydrogel core.

“The combined structural, mechanical and chemical properties of the device we used kept other cells in the mice from completely isolating the implant and, essentially, choking it off and making it ineffective,” said Minglin Ma, a professor of biomedical engineering at Cornell, in a press release.

After implanting the nanoscale devices in mice, they removed them after roughly six months to confirm the cells were still functional. They were.